Some of the most important populations in human history left no direct descendants. They're ghosts. We know they existed only because they left genetic traces in other populations. Using a statistical framework called f-statistics, we can detect these ghosts and even estimate how much ancestry they contributed to populations alive today.

In this post, I'll walk through detecting four ghost populations using public ancient DNA data: Basal Eurasians, Denisovans, Neanderthals, and the African "Ghost Modern" population. All the code is reproducible using the AADR dataset and the admixtools2 R package.

Why I Wanted to Try This

I first encountered ghost populations through the Ancient North Eurasians in a popular genetics book (I can't remember which one, which probably says something about my organizational skills). The idea that you could statistically discover a population that left no remains, just by looking at patterns in the DNA of their descendants, fascinated me. It felt like detective work with math.

My general approach when something like this catches my interest is to go read the original papers, figure out what tools the researchers used, and then try to reproduce the analysis myself. Not because I expect to discover anything new, but because doing it yourself is the fastest way to actually understand what's happening.

To make this kind of exploration practical, I've built up a local collection of common reference datasets: HGDP, 1000 Genomes, SGDP, and AADR. Having these on hand means I can test ideas immediately without spending hours (or days) waiting for multi-gigabyte downloads. It's the difference between "I wonder if..." and actually finding out.

The Key Idea (No Math Required)

Here's the core insight that makes ghost detection work:

When populations split apart and stop interbreeding, they start accumulating different random genetic changes. It's like two branches of a family that move to different countries. Over generations, they'll develop their own traditions, recipes, and quirks that the other branch doesn't have.

The longer two populations have been separated, the more different they become. Closely related populations share more genetic variants. Distantly related populations share fewer.

So if we see a population that shares unexpectedly few genetic variants with another group, fewer than their family tree would predict, something's off. They must have ancestry from somewhere else. Somewhere we haven't sampled. A ghost.

The ghost detector question: "Does this population fit where we think it belongs in the family tree? Or does it have secret ancestry from somewhere else?"

Quick Glossary

Before we dive in, here are the key terms you'll encounter:

- Allele: A variant of a gene. For example, there are different alleles for eye color: one might code for blue eyes, another for brown.

- Allele frequency: How common a particular variant is in a population. If 30% of a population has the "blue eye" allele, that's the allele frequency.

- Genetic drift: Random changes in allele frequencies over generations. Like a coin flip: sometimes an allele gets more common just by chance, sometimes it disappears.

- Gene flow: When people from different populations have children together, mixing their genetic variants.

- Z-score: A measure of how confident we are in a result. |Z| > 3 means "we're very confident this is real, not random noise," roughly a 99.7% confidence level.

- Outgroup: A distantly related population we use as a reference point (like using a chimp to compare human populations).

What Are Ghost Populations?

A ghost population is any ancestral group that contributed DNA to people alive today (or to ancient people we've sampled) but left no remains we can directly sequence. Sometimes we discover them later. Denisovans were a "ghost" until we found a finger bone in a Siberian cave and sequenced it. Other times, like the Basal Eurasians, we may never find direct remains.

Ghosts reveal themselves through patterns that don't fit the family tree. If population A should be closely related to population B based on geography and history, but their DNA says otherwise, there's a ghost in the picture.

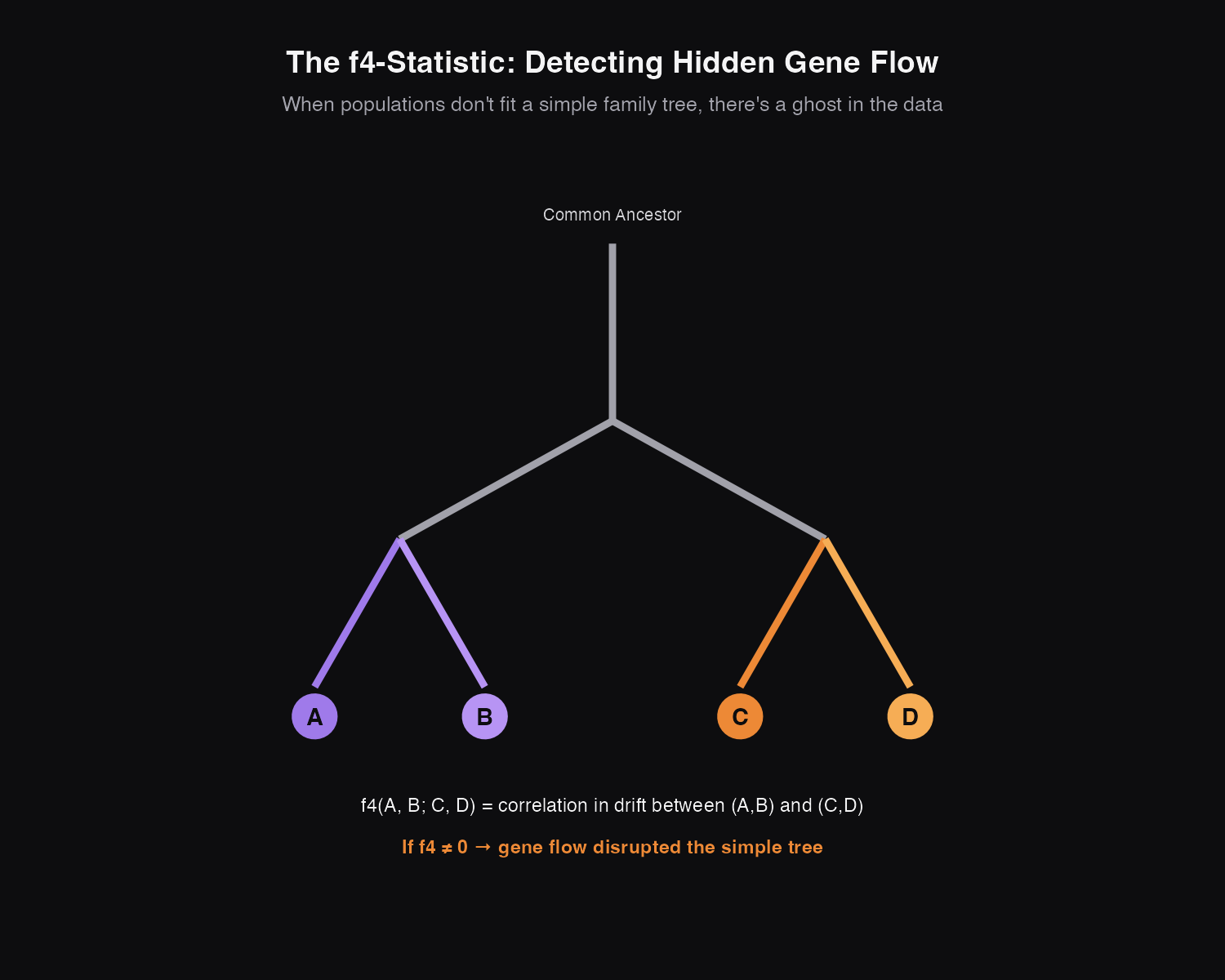

The f4-Statistic: How It Works

The f4-statistic is our ghost detector. It asks: "Do these four populations fit a simple family tree?"

Imagine four populations arranged in a tree. If there's been no mixing between branches, certain patterns should hold. When they don't, the f4-statistic catches it.

Technically, for four populations A, B, C, D:

f4(A, B; C, D) = E[(a - b)(c - d)]This measures whether the genetic differences between A and B are correlated with the differences between C and D. In a simple tree with no gene flow, this should be zero. When it's not zero, something interesting happened, usually gene flow from a population we haven't accounted for.

Reading f4 results: The Z-score tells you if the result is statistically significant. |Z| > 3 means "this pattern is real." The sign (positive or negative) tells you which population has the extra ancestry.

Setting Up the Analysis

We'll use the Allen Ancient DNA Resource (AADR), which contains genetic data from over 17,000 ancient and modern individuals. First, install the required packages:

# Install admixtools2 from GitHub

install.packages("remotes")

remotes::install_github("uqrmaie1/admixtools")

# Load libraries

library(admixtools)

library(dplyr)

# Set path to AADR data (eigenstrat format)

prefix <- "/path/to/v62.0_1240k_public"The AADR data includes individuals labeled by population. For our analyses, we'll use populations like Mbuti.DG (African outgroup), Han.DG (East Asian), and various ancient samples.

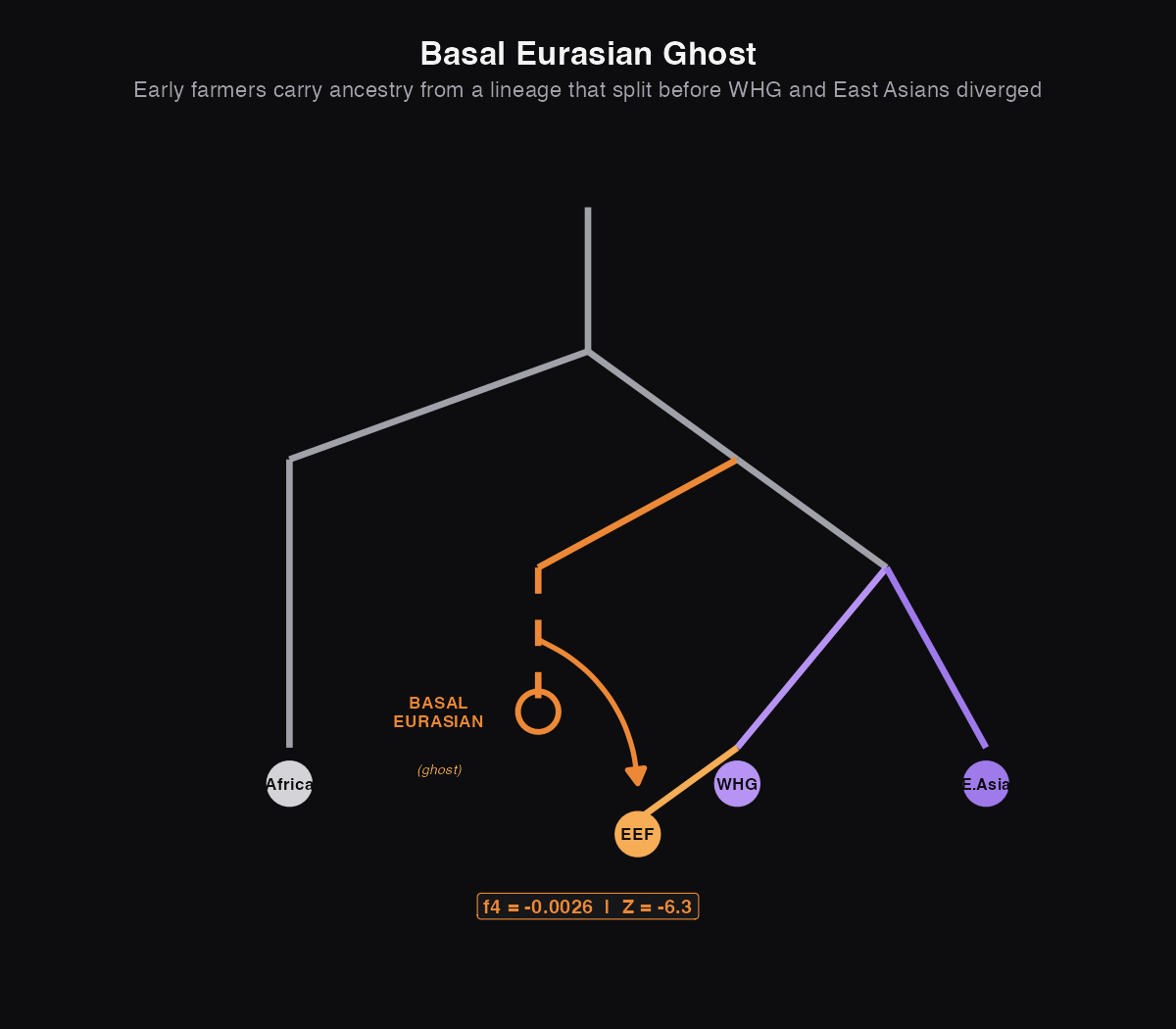

Ghost 1: Basal Eurasians

The Basal Eurasians are perhaps the most elegant ghost story in human genetics. Here's the puzzle that revealed them:

When humans left Africa, we'd expect all their descendants to be roughly equally related to each other. Europeans and East Asians should share the same amount of genetic similarity, since they both descend from that same out-of-Africa group.

But the first farmers in Europe (from Anatolia, modern-day Turkey) share fewer genetic variants with East Asians than European hunter-gatherers do. That's weird. It's like finding out your cousin is less related to your uncle than you are. That shouldn't happen in a simple family tree.

The solution: those early farmers must have ancestry from a population that split off even earlier, before the ancestors of East Asians and European hunter-gatherers diverged. This "Basal Eurasian" lineage diluted their connection to East Asians. We've never found their bones, but their genetic signature is unmistakable.

The Test

# Test for Basal Eurasian ancestry in Anatolian Neolithic

# If Anatolia_N has Basal ancestry, they should share FEWER

# alleles with East Asians than WHG does

f4_basal <- f4(

prefix,

pop1 = "Mbuti.DG", # African outgroup

pop2 = "Han.DG", # East Asian

pop3 = "Luxembourg_Mesolithic.DG", # WHG (Loschbour)

pop4 = "Turkey_Marmara_Barcin_N.DG" # Anatolian Neolithic

)

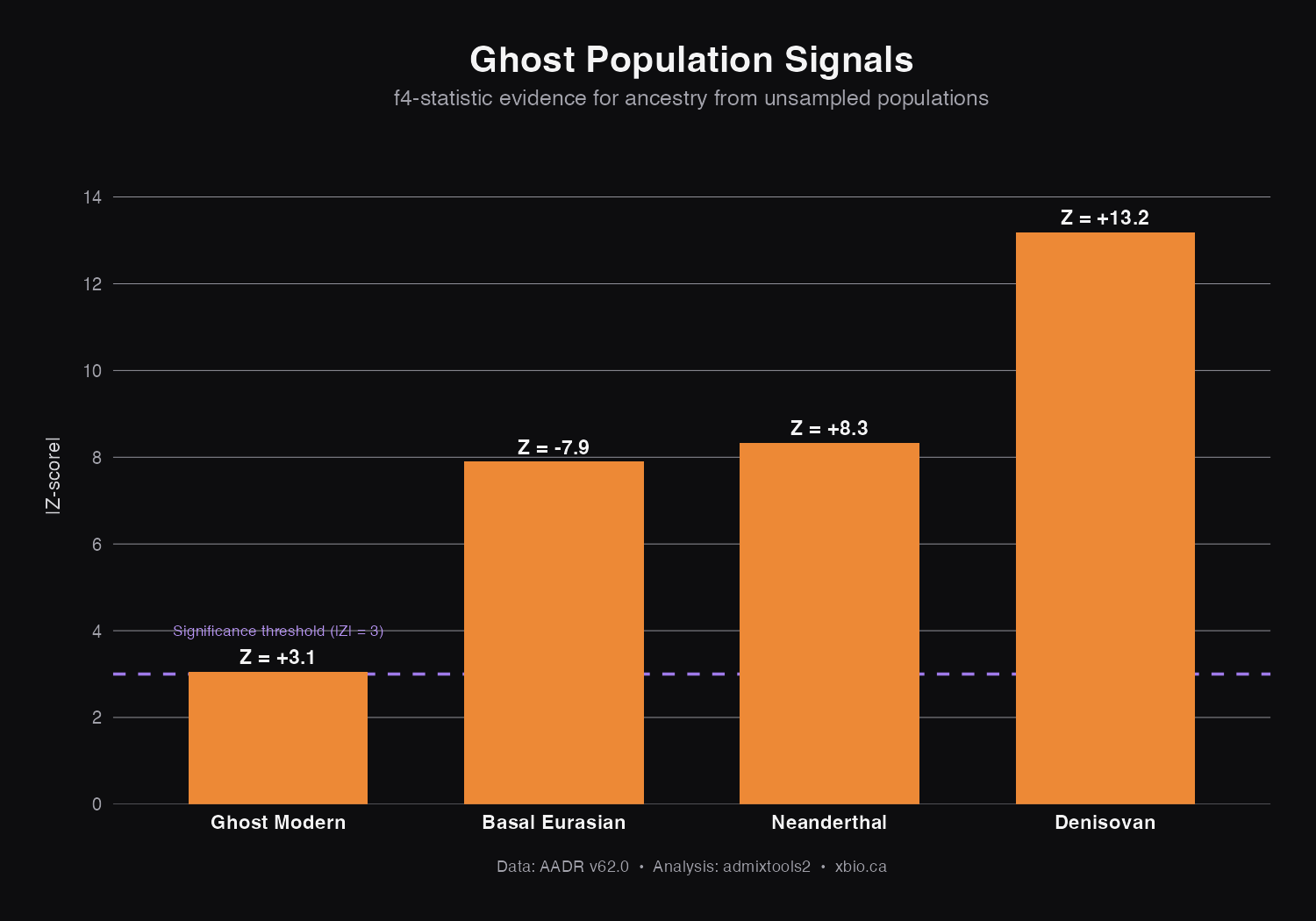

print(f4_basal)Results

| Test | f4 | Z-score |

|---|---|---|

| f4(Mbuti, Han; WHG, Anatolia_N) | -0.00261 | -6.31 |

| f4(Mbuti, Han; WHG, Iran_N) | -0.00294 | -7.90 |

What this means: The negative f4 confirms our suspicion: Anatolian farmers share fewer genetic variants with East Asians than hunter-gatherers do. The Z-score of -6.31 means we're extremely confident this is real (way above our threshold of 3). The early farmers definitely have ancestry from somewhere else.

Iran Neolithic shows an even stronger signal (Z = -7.90), suggesting they have even more Basal Eurasian ancestry than Anatolian farmers.

Confirming with qpAdm

We can go further and try to model Anatolian Neolithic as descending from known populations:

# Try to model Anatolia_N from WHG alone

model1 <- qpadm(

prefix,

target = "Turkey_Marmara_Barcin_N.DG",

left = c("Luxembourg_Mesolithic.DG"),

right = c("Mbuti.DG", "Han.DG", "Russia_MA1_UP.SG")

)

# p-value: 3.99e-15 - MODEL REJECTED

# Model with WHG + Iran_N (Basal proxy)

model2 <- qpadm(

prefix,

target = "Turkey_Marmara_Barcin_N.DG",

left = c("Luxembourg_Mesolithic.DG", "Iran_GanjDareh_N.AG"),

right = c("Mbuti.DG", "Han.DG", "Russia_MA1_UP.SG")

)

# p-value: 0.37 - MODEL FITS (11% WHG + 89% Iran_N)Anatolian Neolithic cannot be modeled from WHG-like ancestry alone (p = 4×10-15). But when we add Iran Neolithic as a source, the model fits. This is because Iran Neolithic also carries Basal Eurasian ancestry.

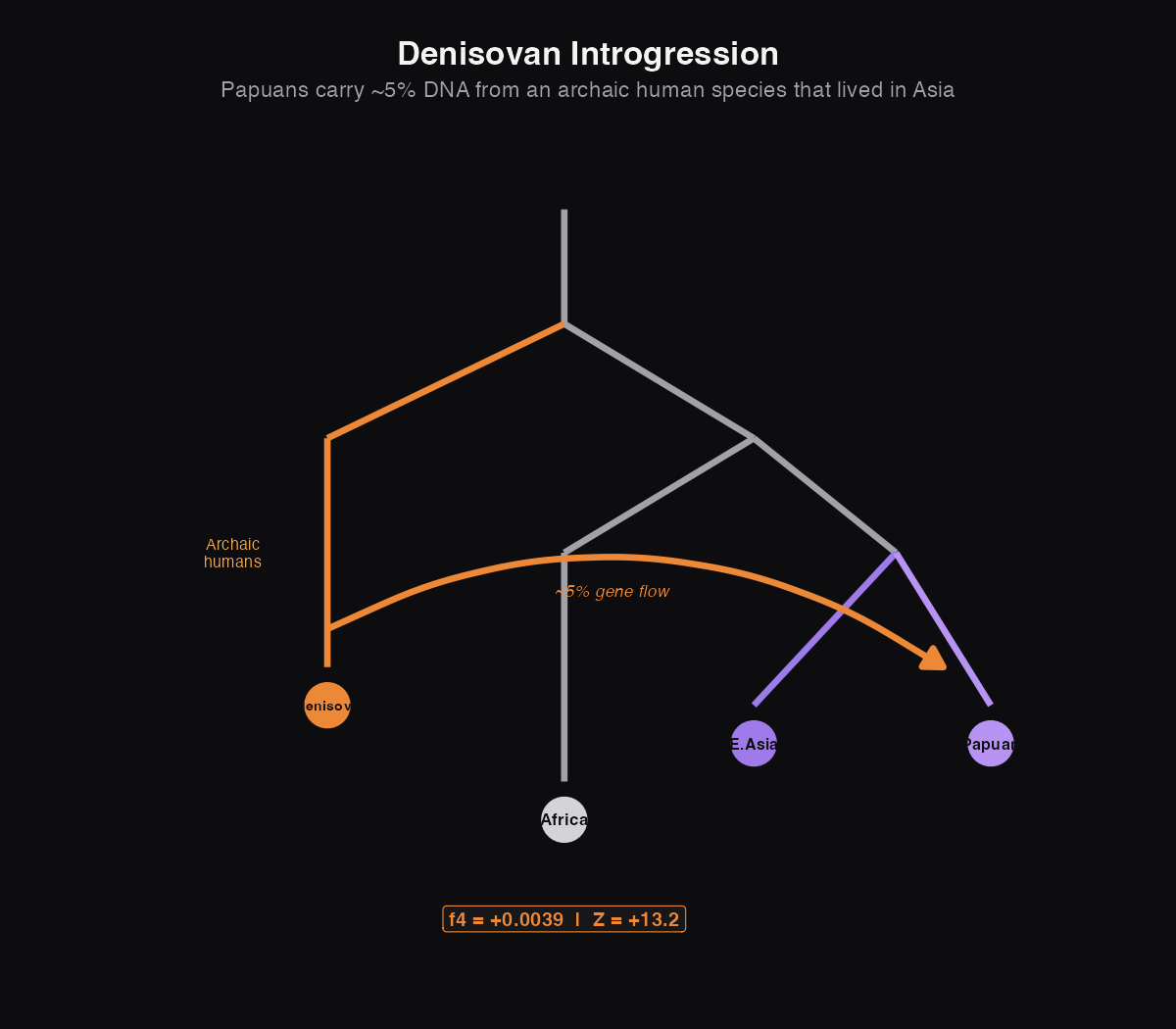

Ghost 2: Denisovans in Oceanians

Denisovans are our success story: a ghost that became real. For years, geneticists could see that Papuans and Aboriginal Australians had DNA from something that wasn't quite human, but they didn't know what. Then in 2010, scientists sequenced a finger bone from a Siberian cave and finally met the Denisovans.

Today we know that people from Oceania (Papua New Guinea, Australia, and nearby islands) carry about 5% Denisovan DNA, the result of interbreeding tens of thousands of years ago. Most other populations have essentially none. This is archaic introgression: gene flow from a different human species into our own.

The Test

# Test for Denisovan ancestry in Papuans vs Han

# Positive f4 = Papuans share MORE with Denisova than Han

f4_denisovan <- f4(

prefix,

pop1 = "Mbuti.DG", # African outgroup

pop2 = "Denisova.DG", # Denisovan (we have their DNA!)

pop3 = "Han.DG", # East Asian

pop4 = "Papuan.DG" # Oceanian

)Results

| Test | f4 | Z-score |

|---|---|---|

| f4(Mbuti, Denisova; Han, Papuan) | +0.00387 | 13.19 |

| f4(Mbuti, Denisova; Han, Australian) | +0.00397 | 12.48 |

| f4(Mbuti, Denisova; Han, French) | -0.00033 | -1.95 |

What this means: The positive f4 with Z = 13.19 is enormous, one of the strongest signals in human population genetics. Papuans share dramatically more genetic variants with Denisovans than Han Chinese do. Aboriginal Australians show the same pattern (Z = 12.48). Meanwhile, Europeans show no excess Denisovan ancestry (Z = -1.95 is below our significance threshold).

This geographic pattern tells a story: the ancestors of Papuans and Australians interbred with Denisovans somewhere in Southeast Asia or Oceania, after they had already split from the ancestors of East Asians and Europeans.

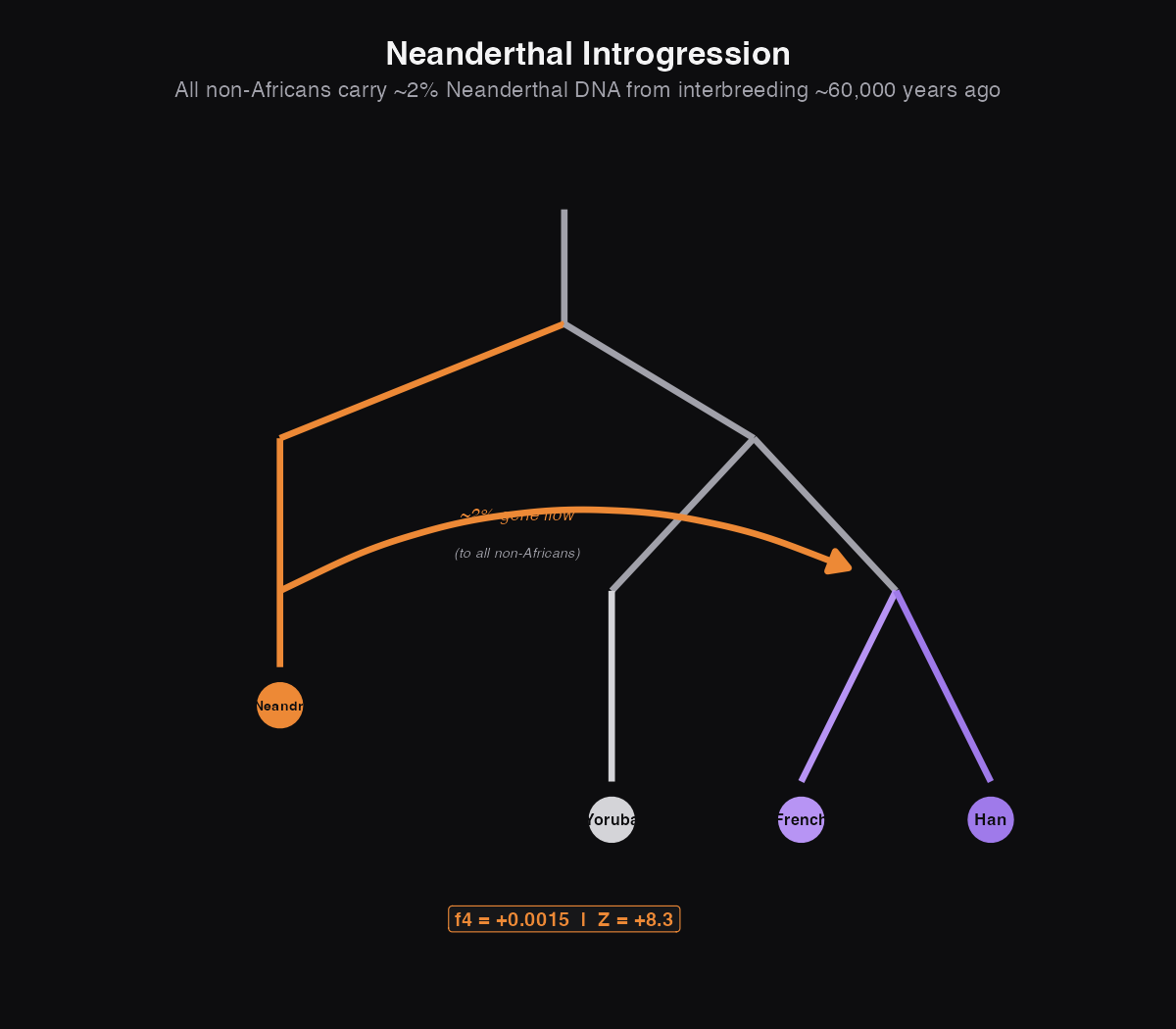

Ghost 3: Neanderthals in Non-Africans

Neanderthals are the most famous "other humans." They lived in Europe and western Asia for hundreds of thousands of years before modern humans arrived. When the first Neanderthal genome was sequenced in 2010, the big surprise wasn't that we could read ancient DNA. It was that everyone outside of Africa carries 1-2% Neanderthal DNA.

When modern humans left Africa around 60,000 years ago, they met and interbred with Neanderthals. That mixing happened early, before the ancestors of Europeans and East Asians split apart, which is why both groups carry similar amounts of Neanderthal ancestry today.

The Test

# Test for Neanderthal ancestry in non-Africans

# Using Chimp as outgroup instead of Mbuti

f4_neanderthal <- f4(

prefix,

pop1 = "Chimp.REF", # Outgroup

pop2 = "Vindija_Neanderthal.DG", # Neanderthal

pop3 = "Yoruba.DG", # African

pop4 = "Han.DG" # Non-African

)Results

| Test | f4 | Z-score |

|---|---|---|

| f4(Chimp, Neanderthal; Yoruba, Han) | +0.00163 | 7.59 |

| f4(Chimp, Neanderthal; Yoruba, French) | +0.00149 | 8.33 |

| f4(Chimp, Neanderthal; French, Han) | +0.00014 | 0.82 |

What this means: Both Han Chinese and French share significantly more genetic variants with Neanderthals than Yoruba (West Africans) do. Z-scores above 7 are rock-solid evidence. But when we compare French to Han directly (Z = 0.82), there's no significant difference. They have the same amount of Neanderthal ancestry.

This tells us exactly when the interbreeding happened: after humans left Africa (which is why Africans don't have Neanderthal DNA) but before Europeans and East Asians split apart (which is why both groups have the same amount).

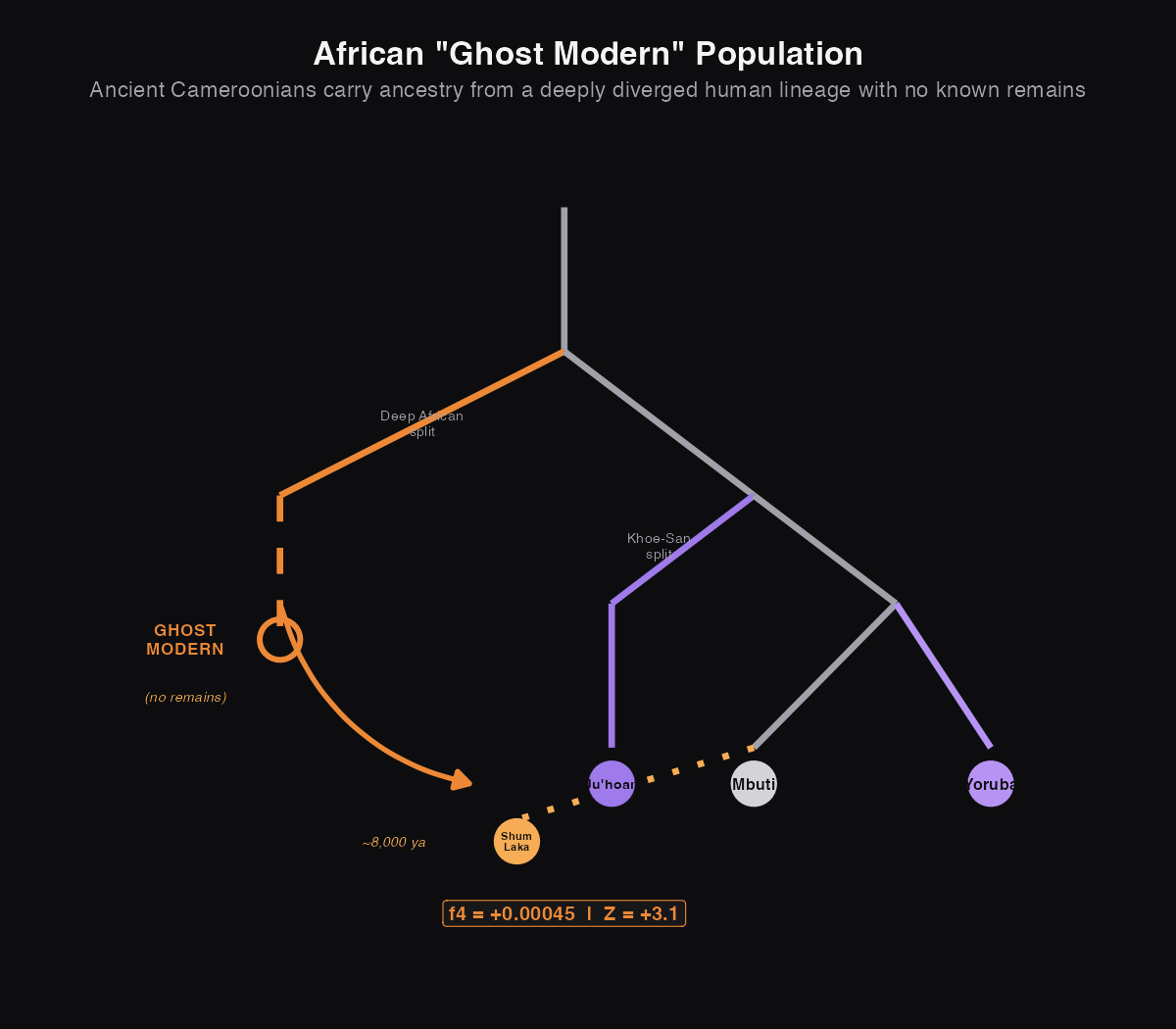

Ghost 4: The African "Ghost Modern" Population

The three ghosts above all involve ancestry outside Africa. But Africa (where our species originated and where humans have lived the longest) has its own ghosts.

When scientists sequenced ancient DNA from Shum Laka rock shelter in Cameroon (about 8,000 years old), they found something unexpected: these ancient Africans carried ancestry from a human lineage that split off extremely early, possibly around the same time the ancestors of the Khoe-San peoples (like the San and Ju|'hoansi) diverged from everyone else.

This isn't like Denisovans or Neanderthals; it's not a different species. It's a "ghost modern" human population: fully human, but from a branch of the family tree we've never directly sampled. Their DNA shows up in ancient Cameroonians but has been mostly diluted in present-day West Africans, probably through later population movements like the Bantu expansion.

The Test

# Test for Ghost Modern ancestry using Khoe-San as deep African reference

# If Shum Laka has Ghost Modern ancestry, they should share FEWER

# alleles with Khoe-San than present-day West Africans do

f4_ghost_modern <- f4(

prefix,

pop1 = "Chimp.REF", # Outgroup

pop2 = "Ju_hoan_North.DG", # Khoe-San (deep African reference)

pop3 = "Cameroon_ShumLaka_SMA.AG", # Ancient Cameroon (~8 kya)

pop4 = "Yoruba.DG" # Present-day West African

)Results

| Test | f4 | Z-score |

|---|---|---|

| f4(Chimp, Ju_hoan; ShumLaka, Yoruba) | +0.00045 | 3.06 |

| f4(Chimp, Ju_hoan; ShumLaka, Mende) | -0.00024 | -1.27 |

| f4(Chimp, Ju_hoan; ShumLaka, Mbuti) | ~0 | 0.09 |

What this means: The positive f4 with Z = 3.06 (just above our threshold of 3) reveals something surprising: present-day Yoruba are more closely related to the Khoe-San than these 8,000-year-old Cameroonians were. That's backwards from what you'd expect geographically, since Cameroon is closer to southern Africa than Nigeria is.

The explanation: the ancient Shum Laka people had ancestry from an even older branch of the human family tree. Present-day West Africans have less of this deep ancestry because later migrations (especially the Bantu expansion, which spread farming across Africa) mixed in people from other lineages.

The Mende people from Sierra Leone (Z = -1.27) show a pattern similar to Shum Laka, hinting they may have retained more of this ancient deep ancestry than other West African groups.

Summary: Four Ghosts, One Method

| Ghost Population | Key Test | Z-score | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basal Eurasian | f4(Mbuti, Han; WHG, EEF) | -6.31 | EEF has ancestry from lineage that split before WHG/East Asian common ancestor |

| Denisovan | f4(Mbuti, Denisova; Han, Papuan) | +13.19 | Papuans have ~5% archaic Denisovan ancestry |

| Neanderthal | f4(Chimp, Neanderthal; Yoruba, non-African) | +7.59 | Non-Africans have ~2% archaic Neanderthal ancestry |

| Ghost Modern | f4(Chimp, Ju_hoan; ShumLaka, Yoruba) | +3.06 | Ancient Cameroonians have ancestry from early-diverging modern human lineage |

The same simple question, "Do these populations fit a simple family tree?", detected all four ghosts. When the answer is "no," we've found hidden ancestry. The direction of the f4-statistic tells us which population doesn't fit:

- Negative f4 (like Basal Eurasian): The test population shares fewer variants than expected. They have ancestry from somewhere that diluted their connection to the comparison group.

- Positive f4 (like Denisovan, Neanderthal, Ghost Modern): The test population shares more variants than expected. They have extra ancestry from the reference population.

Tips for Ghost Hunting

The f4-statistic is powerful, but you need to set up your test carefully:

- Pick a good reference point. Your "outgroup" population should be distantly related and uninvolved in the mixing you're testing. For comparing non-African populations, we often use Mbuti (Central African) as a reference. For comparing humans to Neanderthals, we need chimps as a reference point.

- Understand what "zero" means. When f4 = 0, your four populations fit a simple family tree with no unexpected mixing. When f4 ≠ 0, something interesting happened. Your job is to figure out what.

- Run multiple tests. A single test could be explained in different ways. Running several tests from different angles helps you triangulate what actually happened.

- More samples = better results. Ancient DNA is messy and incomplete. Testing multiple individuals from each population, and using well-preserved samples when available, gives you cleaner, more reliable signals.

More Ghosts to Find

This analysis barely scratches the surface. Other ghost populations waiting to be explored include:

- Ancient North Eurasians: A population that contributed ancestry to both Native Americans and Europeans, connecting people on opposite sides of the world

- "Population Y": A mysterious ghost with Australasian-like DNA that somehow shows up in some Amazonian indigenous groups

- Multiple Denisovan groups: There may have been several different Denisovan populations, each contributing to different modern groups

- More African ghosts: Africa has the deepest human genetic diversity, and likely harbors more undiscovered ancient lineages

One important limitation: some ghost populations can't be detected with f4-statistics at all. The West African ghost archaic (a non-human hominin that may have interbred with our ancestors in Africa) requires completely different methods because we have no reference genome to compare against. The methods described here only work when you have at least some idea of what you're looking for.

The tools are freely available, the data is public, and the ghosts are waiting to be found. All you need is curiosity and some R code.

We can detect populations that left no bones, no artifacts, nothing but their DNA scattered across the genomes of their descendants. That's the power of population genetics.

Code and Data

All analyses were performed using:

- AADR v62.0 (Allen Ancient DNA Resource)

- admixtools2 R package

- R 4.5

The complete analysis code is available in my ghost-popgen repository.

References

- Patterson et al. (2012). Ancient Admixture in Human History. Genetics.

- Lazaridis et al. (2014). Ancient human genomes suggest three ancestral populations for present-day Europeans. Nature.

- Reich et al. (2010). Genetic history of an archaic hominin group from Denisova Cave in Siberia. Nature.

- Green et al. (2010). A Draft Sequence of the Neandertal Genome. Science.

- Lipson et al. (2020). Ancient West African foragers in the context of African population history. Nature.

- Durvasula & Sankararaman (2020). Recovering signals of ghost archaic introgression in African populations. Science Advances.